I hope, when you will read this article, the picture of code execution pipeline will be more explicit. We will trace the journey of the code, starting from high-level language to low-level machine instructions. We are going to a deep rabbit hole…

DISCLAIMER: I will not dive into technical details of implementation, which differs from one vendor to another. We will go through a conceptual overview only. Otherwise, the article would take hours to read and months to write.

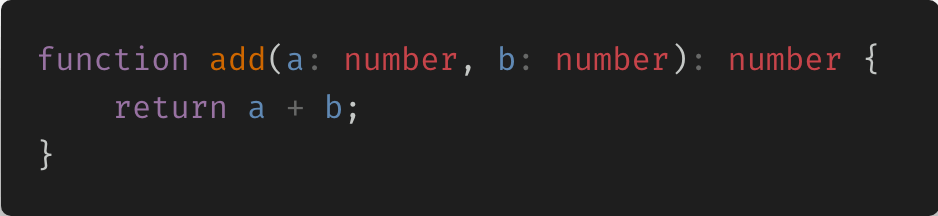

TypeScript

Let us start from one of the high-level languages - TypeScript. I will write the simplest function, from a high-level perspective, the function that adds two numbers.

Why is so simple logic? Because there is a lot of going on under the hood, we need to choose as simplest code as we can to fit the explanation in one article.

Anyway, here is the code in TypeScript that adds 2 numbers:

What do we do with the code we want to run? We compile it!

tsc my-code.ts

NOTE: Some of you may suggest that you can run the TypeScript code without actual compiling, but that is not true. Hooks like ts-node and similar just hiding the compiling process behind the scenes.

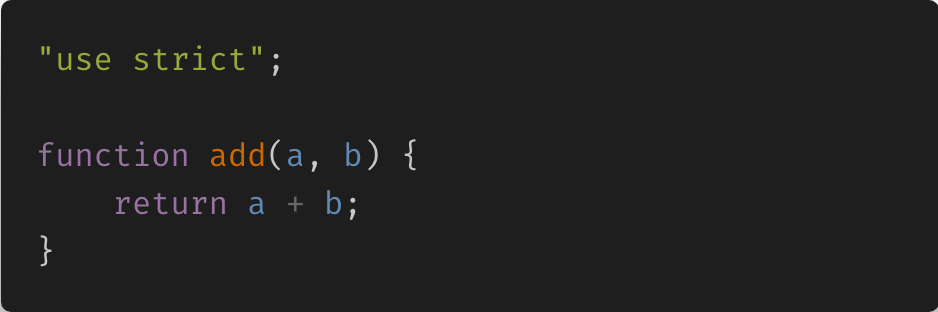

What is the result? You already know - JavaScript!

NOTE: You could get more strange code, depending on the target you were compiling (ES5, ES3 maybe?).

So, what happened? You had an input as a TypeScript code and an output as a JavaScript code, but what is in there between then?

Compiler! Compilers transform the code from one representation to another one.

In our case, TypeScript compiler transforms the TypeScript code into JavaScript code, while checking the types at compile-time, semantics, etc…

Anyway, we got the JavaScript code. What is next?

JavaScript

When you got the JavaScript code from a TypeScript compiler, you need to run it somehow. Let us take Node.js for these purposes and run it:

node my-compiled-code-from-typescript.js

When you run it, you will get a function you can call anytime. Though, what happens with the JavaScript code to make it possible on the computer?

Since we are running it on Node.js, I will take the JavaScript engine from Google - V8.

There is a lot happening under V8 when your JavaScript code is running. However, I will not talk about all of it, only about general compilation.

So, how can we get to know what is happening with our JavaScript code inside V8?

V8 (Ignition)

V8 takes the JavaScript code as a source text. Parses it, analyzes the program, transforms it into an intermediate representation that much better to work with.

Like with the TypeScript before, but now it has JavaScript as an input and another representation of it as an output. The output is a bytecode for the V8 interpreter - Ignition.

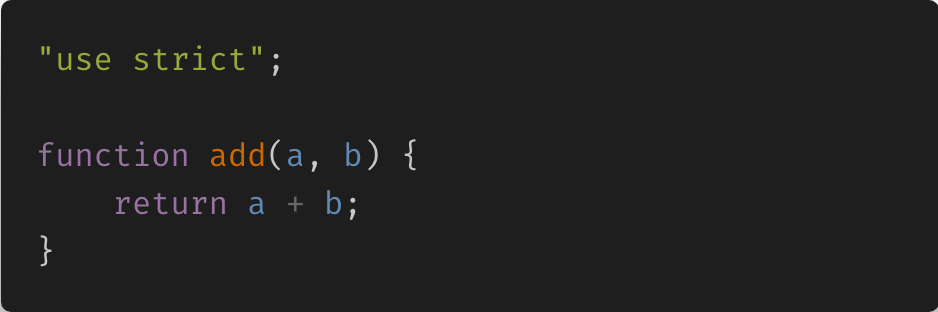

Let me remind our JavaScript code we passed to Node.js (V8):

Now, how can we get the internal representation of this code? How can we get the Ignition bytecode for this?

We can use “special” flags:

node --print-bytecode --print-bytecode-filter=add our-code.js

We use two flags here, print-bytecode and print-bytecode-filter. Their purpose is to print the Ignition bytecode to the console and filter out the bytecode to match only our function, to make the output cleaner.

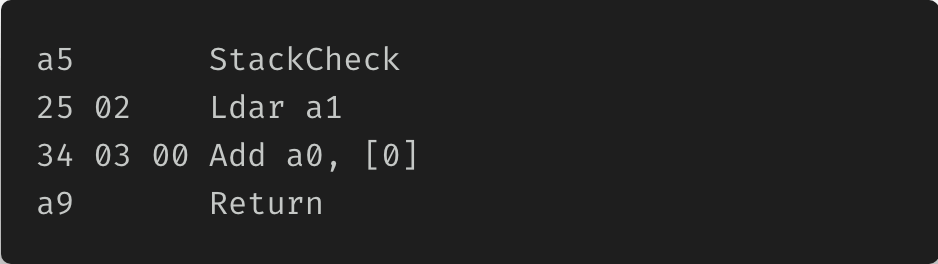

So, what is the representation of our JavaScript code? How does it look like, our next chapter in the journey?

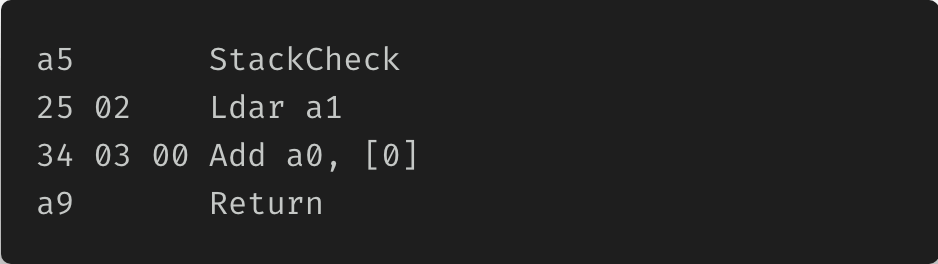

Simple, right?

You have hexadecimal values that represent the operation and its parameters on the left side. Look at it as the constant values somewhere deep in the V8 implementation.

On the right side, you have a mnemonic for the operation, so you don’t get lost in numbers but get a human-readable description of the operation and its parameters.

Let us take a5 and a9. They are simple; they have no arguments. So, if the Ignition sees a5, for example, which is 165 in decimal and 10100101 in binary - it means for Ignition that it needs to execute the StackCheck operation.

The same for a9, but Ignition understands that it have to return the value from accumulator to its caller instead of performing the stack check operation.

Now, more interesting - parameters and how they are passing around. Each operation code has a paging, offset, you name it.

In case with a5 and a9, they have no arguments, that is why there is only 1 byte present. But, we have operation 2 bytes long, even 3 bytes long.

Let us take the operation 2 bytes long - 25 02, which is Ldar operation. Ldar means, load to the accumulator the value from register. Now, imagine that we have an agreement, a contract, which states that if you want to load some value to the accumulator, you need to pass the code for the Ldar operation 1 byte long, afterwards; you need to pass another 1 byte which represents the parameter for the Ldar operation.

And that happening with 25 02. 25 means for Ignition that it have to load something to the accumulator and 02 means that it must take the value from register a1.

Now, let us gather the hard part above, collect our thoughts together and try to debug the bytecode step by step, to prove, that it is doing what we need.

I’ll repeat the code here one more time, so you need not scroll above:

Now, step by step:

- Call the “Stack Check” procedure before the function call. We can ignore this one, you can find more details about it on the Internet.

- Load value to the accumulator from register a1. In our case, a1 maps to argument b in our function, because it has the index 1 in the arguments list. So, the value of b goes to the accumulator.

- Add value from the accumulator to the value in a0. a0 holds the value of argument a, because it has an index 0 in arguments list. The result writes back to the accumulator.

- Return the value from the accumulator back to the caller.

So, it does what we intend to do. Take two parameters, add them together and the result return to its caller.

This is the place where we could stop, because we have a bytecode that interpreter can execute. But, let us going deeper.

The bytecode is cross-target. It means, that the bytecode knows nothing about the real CPU it is running on. So, now, we need to think about transforming the bytecode to some real instructions for the concrete CPU your computer is working on.

V8 (Turbofan)

Things are ok with Ignition, it interprets the bytecode, it works, everyone is happy. Until, it turns out that the code is called often, leading to performance looses.

For such cases, we need to transform it to the representation close to the real CPU ISA (Instruction Set Architecture).

We need to compile the V8 bytecode from Ignition to the Assembly language of the concrete CPU your computer is working on.

And you know what? We can get its representation.

Do you remember our “special” flags? Let us use them again:

node --print-opt-code --print-opt-code-filter=add our-code.js

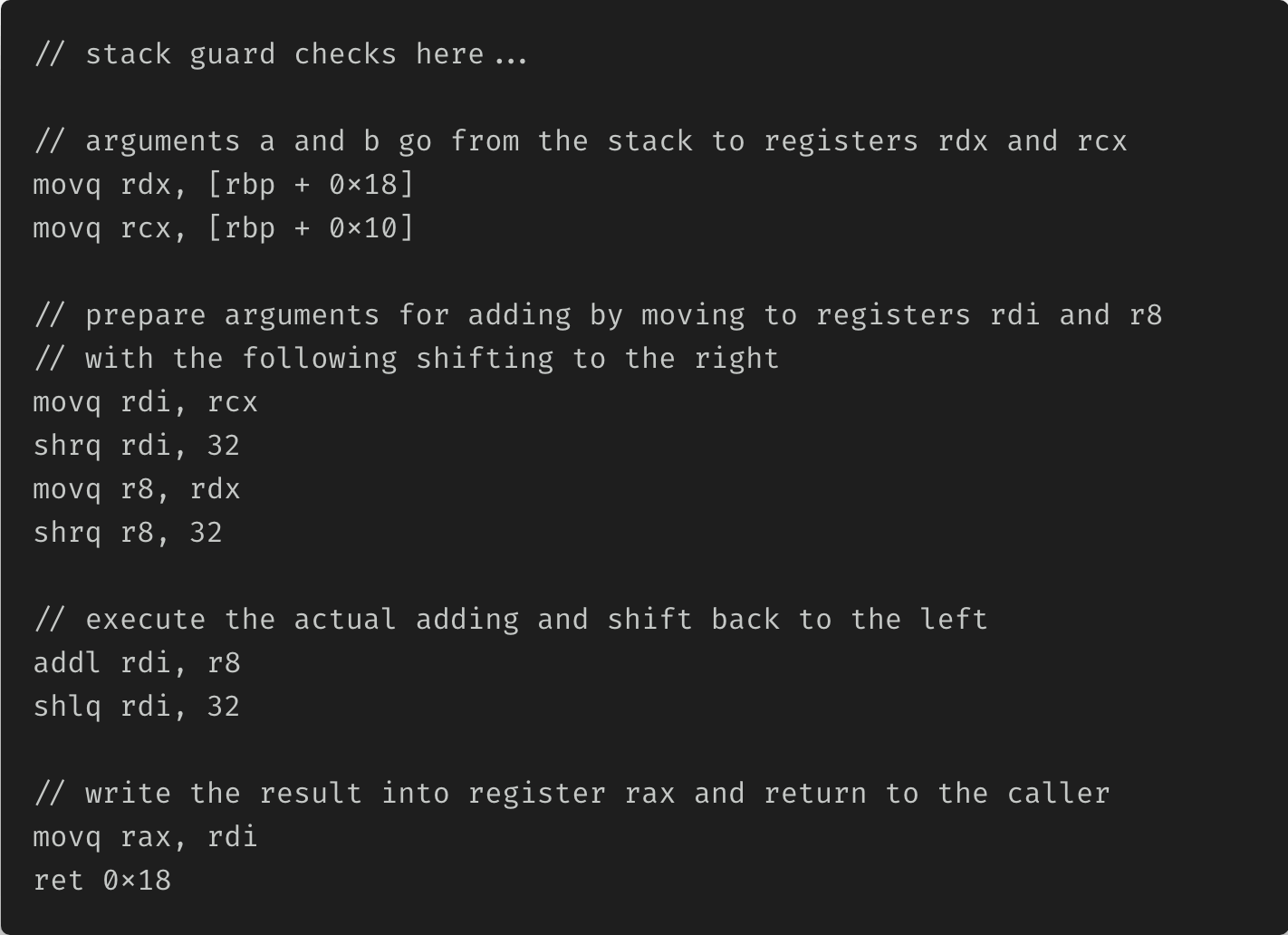

These flags mean that we want to get the output of Turbofan compiler, an assembly that targets your CPU, and we want to filter out the code to match only our function for adding two numbers. In my case, I got a lot of instructions which size in total is 200 bytes, so I will strip some instructions, which are not important for us (guard checks, bailouts, etc):

Now, let us go through it step by step:

- Our parameters are laying on the stack. So, we need to get them to some registers in the CPU. For achieving this, V8 using movq instruction with the [] syntax, which means the address in memory. In our case, it goes to two destinations: [rbp + 0x18] and [rbp + 0x10].

- When V8 put the values from the stack to registers, it makes some guard checks, to be sure that everything is ok with data. If so, it uses another movq instruction to move the values into registers rdi and r8.

- The simplest part - addl instruction to add values from two registers and the result put back into register rdi.

- The last step - return to the caller. But before, it writes the value of adding to register rax. From there, from register rax, V8 will retrieve the result of adding two numbers outside the function.

It is tough, right? But, we are almost there. We are almost at the end of the journey, so brace yourself.

We have an assembly instructions, what to do with them?

Assembler

Each CPU has its own ISA (Instruction Set Architecture). When hardware engineers are designing the chip, they are thinking about a lot of things: which gates to use, how to wire them up, how to make it faster and so on and so forth.

Also, when the chip with all these wires is done, engineers are working on the assembler for the CPU.

What is assembler? Assembler is a program, that can translate assembly code, like above, to the instruction set for their CPU.

Worth noting that an assembly code is just a mnemonics for binary values. Like with Ignition bytecode before. We saw that it has binary values and has a human-readable description of the value. The same here, assembly code is just a human-readable description for a binary value, hardware engineers came up.

Now, we need to transform our human-readable descriptions to the actual binary values. We are passing the assembly code to assembler.

Machine Instructions

The result is one-s and zero-s, somehow combined in a way, CPU can understand, like:

0101101001010110

0110100010110101

1010001101101001

_NOTE: these are not real binary values from the assembly code above. These are

just made up values to show you how it would look like, the compiled assembly

code for 16-bit CPU. The reason is simple; I don’t see any sense to provide you

200 bytes of binary values just to show you the result of the assembler, it will

take 200 _ 8 = 1600 characters on the screen.*

But, that is starting blowing your mind, I guess? All you wanted to do is just add two numbers, but you ended up in some binary sequences.

Well, these binary sequences are making sense for your CPU now. Our program for adding two numbers has a binary representation and even is stored somewhere in memory, waiting for someone to come up and execute it.

This “someone” is a CPU - Central Processing Unit. It goes to the memory step by step, register by register, loads the binary instruction to its decoder and executes it. Afterwards, state of the CPU is changing, according to the instruction it have executed.

Then, it takes another one binary value from another memory region. Sends it to decoder again, updates the state of the CPU and so on and so forth…

But, that is the story for another article. We already discussed too much here.

P.S

Thanks for reading!

If you love to read more about such things, please, ping me on Twitter - @ghaiklor. Tell me your feedback, leave comments, what you want to read about next?

Eugene Obrezkov, Software Engineer, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Comments